Genesis 22

Genesis 22

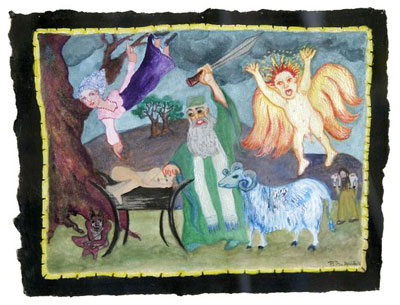

The Sacrifice of Isaac,

The Akedah,

Or

Is This Really What a Test of Faith Looks Like?

There are few words that I could use to begin any conversation or discussion of this chapter, mostly because there are already so many words in print concerning the content of this passage. Suffice to say that there are few stories in the Old Testament that are both as controversial and foundational to the Jewish and Christian perceptions of faith as when God asks Abraham to sacrifice Isaac upon Mount Moriah. Thus, like with similar chapters and/or stories that can be quite difficult to interpret and translate (to anyone, no matter their age), I will be selecting some quality commentary selections for the reader to peruse along with some reflection of my own, as opposed to an in-depth lesson. After that, I will present some guidelines that teachers can use in telling this story to the students in their classes.

Genesis – Robert Alter

“2. Your son, your only one, whom you love, Isaac. The Hebrew syntactic chain is exquisitely forged to carry a dramatic burden, and the sundry attempts of English translators from the King James Version to the present to rearrange it are misguided. The classical Midrash, followed by Rashi, beautifully catches the resonance of the order of terms. Rashi’s concise version is as follows: “Your son. He said to Him, ‘I have two sons.’ He said to him, ‘Your only one.’ He said, ‘This one is an only one to his mother and this one is an only one to his mother.’ He said to him, ‘Whom you love.’ He said to him, ‘I love both of them.’ He said to him, ‘Isaac.’” Although the human object of God’s terrible imperative does not actually speak in the biblical text, this midrashic dialogue demonstrates a fine responsiveness to how the tense stance of the addressee is intimated through the words of the addresser in a one-sided dialogue.” (p103)

“7. The fire and the wood. A moment earlier, we saw the boy loaded with the firewood, the father carrying the fire and butcher knife. As Gerhard Von Rad aptly remarks, ‘He himself carries the dangerous objects with which the boy could hurt himself, the torch and the knife.’ But now, as Isaac questions his father, he passes in silence over the one object that would have seemed scariest to him, however unwitting he may have been of his father’s intentions – the sharp-edged butcher knife.” (p105)

“11. And the Lord’s messenger called out to him from the heavens. This is nearly identical with the calling-out to Hagar in 21:17. In fact, a whole configuration of parallels between the two stories involved. Each of Abraham’s sons is threatened with death in the wilderness, one in the presence of his mother, the other in the presence (and by the hand) of his father. In each case the angel intervenes at the critical moment, referring to the son fondly as na’ar, “lad.” At the center of the story, Abraham’s hand holds the knife, Hagar is enjoined to “hold her hand” (the literal meaning of the Hebrew) on the lad. In the end, each of the sons is promised to become progenitor of a great people, the threat to Abraham’s continuity having been averted.” (p106)

The Jewish Study Bible: JPS Tanakh Translation

“22.1-19: Abraham’s last and greatest test. This magnificently told story, known in Judaism as the ‘Akedah’ (“binding”), is one of the gems of biblical narrative. It also comes to occupy a central role in rabbinic theology and eventually to be incorporated into the daily liturgy. Jewish tradition regards the Akedah as the tenth and climatic test of Abraham, the first Jew.” (p45)

“2: The order of the Heb[rew] is ‘your son, your favored one, the one whom you love, Isaac’ and indicates the increasing tension. Not only is Isaac the son upon whom Abraham’s life has centered; he also loves him. If Abraham did not love Isaac, the commandment to sacrifice him would not have constituted much of a test. The expression to go (“lekh-lekha”), which otherwise occurs only in [Genesis] 12:1, the initial command to Abraham, ties this narrative to the beginning of Abraham’s dealings with God.” (p45)

“3: … Some have wondered why Abraham, who protested God’s decision to destroy the innocent with the guilty in Sodom (18.22-32), here obeys without objection. The essence of the answer is that the context in ch[apter] 18 is forensic, whereas the context of the Akedah is sacrificial. A sacrifice is not an execution, and in a sacrificial context the unblemished condition of the one offered does not detract from, but rather commends, the act.” (p46)

“12: In the Tanakh, the ‘fear of God’ denotes an active obedience to the divine will. God is now able to call the last trial of Abraham off because Abraham has demonstrated that this obedience is uppermost for him, surpassing even his paternal love for Isaac.” (p46)

The Torah: A Modern Commentary – W. Gunther Plaut

“Few narrative sections of the Torah have been subjected to as much comment and study as the Akedah (binding [of Isaac]). Jewish, Chrisitan, and Moslem theologies have tried to fathom its intention. In his introduction to this chapter, Abarbanel called the story ‘worthier of study and investigation than any other section.’ Its subject matter ranges from the God who tests to the man who is tested, from the nature of faith to the demands it makes, and it considers many other questions as well. Says Von Rad: ‘One should renounce any attempt to discover one basic idea as the meaning of the whole. There are many levels of meaning.

The literary pattern of the section is reminiscent of the first passage of the Abraham story: A divine command is issued asking Abraham to set out toward an as yet undetermined place. The same unusual reflexive phrasing (see Gen 12:1) contains the directive lech-lecha (go forth). It is almost as though the external elements of the tale, while clear enough, hide deeper problems under the cover of simpler words.” (p145)

Genesis: Interpretation – Walter Brueggemann

“… In our present text, unexpected things happen. Only now do we see how serious faith is. This narrative shows us that we do not have a tale of origins, but a story of anguished faith. The narrative holds rich promise for exposition. But it is notoriously difficult to interpret. Its difficulty begins in the aversion immediately felt for a God who will command the murder of a son.” (p185)

“The life of Abraham, then, is set by this text in the midst of the contradiction between the testing of God and the providing of God; between the sovereign freedom which requires complete obedience and the gracious faithfulness which gives good gifts; between the command and the promise; and between the word of death which takes away and the word of live which gives. The call to Abraham is a call to live in the presence of this God who moves both toward us and apart from us (cf. Jer. 23:23). Faithful people will be tempted to want only half of it. Most complacent religion will want a God who provides, not a God who tests. Some in bitterness will want a God who tests but refuse the generous providing. Some in cynical modernity will regard both affirmations as silly, presuming we must answer to none and rely upon none, for we are both free and competent. But father Abraham confessed himself not free of the testing and not competent for his own provision.” (p192-193)

“The text asserts that God is this way with his people. There are deep problems with affirming that God both tests and provides. The problems are especially acute for those who seek a “reasonableness” in their God. But this text does not flinch before nor pause at the unreasonableness of the story. God is not a logical premise who must perform in rational consistency. God is a free lord who comes as he will. As the ‘high and holy One,’ God tests to identify his people, to discern who is serious about faith and to know in whose lives he will be fully God. And as the one among the ‘humble and contrite,’ God provides, giving good gifts which cannot be explained or even expected. We are not permitted by this narrative to choose between these characteristics of God (cf. Isa. 57:15). (p193)