Genesis 29:1-14

Jacob Arrives in Paddan Aram

Or

Jacob Really Knows How to Show Off to Get the Girl

One of the primary reasons I’ve come to enjoy the Story of the Patriarchs throughout the book of Genesis is that it is such a distinct microcosm of world history. Nations are born, nations develop, nations propagate internally and externally, the strength of the nations ebbs and flows, nations experience conflict internally and externally, and the story repeats itself endlessly. Moreover, nary three generations have finished with this story before the events are reprised with a new crop of descendents. It is as if the author(s) of the story would like for whoever is reading the tale or listening to it being told to realize the patterns and the various levels of significance present within each pattern.

But what makes the story of the Covenant so great is that, much like all other epic and archetypal narratives throughout literary and world history, these lessons being communicated are not spelled out in specific terms. They don’t scream, “Hey you! Pay attention here! Remember this!” And we should be glad of this fact. And yes, autocratic leaders throughout time immemorial have regularly concocted stories that openly declare their intentions and tell people exactly what to do and not do, believe and not believe. However, history also tells us that (with few exceptions) such belief systems have a rather short shelf life. Thus, we must perpetually approach the Story of the Patriarchs with reverence and awe, for we often aren’t aware of what ideas and impressions our current perusal of any given passage in the text might work their way into our imaginations.

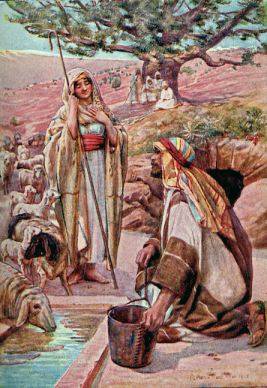

So, if you’ve followed my train of thought this far, I ask you to walk with me into this bit of text – Jacob’s arrival at his mother’s home and subsequent conversation with the shepherds, Rachel, and Uncle Laban, who is both Rachel’s father and Rebekah’s brother. Jacob continues with his journey across the desert, seeking out the family members that his parents instructed him to locate. In so traversing the vast sandy peninsula, he comes across a well, covered by a large stone and surrounded by several shepherds and their sheep. As such wells are common places for people to meet, converse, barter, and trade, it is proper for Jacob to approach these shepherds and inquire of them where he was and if they knew who Laban was. (Coogan, et al; p51) However, Jacob seems to have found a collection of lazy shepherds who were seemingly unable and unwilling to remove the large stone protecting the well so that they may water their sheep and continue on with the rest of their daily chores. (Hamilton, p253)

The subsequent scene is a shortened, but altogether mirrored version of The Servant’s mission to locate a wife for Isaac. (Berlin & Brettler, p59) It seems that not only do these shepherds know of Laban, they point out to Jacob that Rachel, Laban’s daughter, is a shepherdess who is walking their way. Jacob sees Rachel and his reaction is one of “Samsonesque” strength as he removes the stone covering the well on his own, a task that typically requires the strength of two or three men. (Hamilton, p255) It seems that Jacob is intent upon impressing Rachel with his physical abilities and willingness to serve others – without the stone being removed, neither Rachel or the stationary shepherds would be able to water their sheep.

After accomplishing such a feat, Jacob is so overcome with emotion that he kisses Rachel and weeps upon her shoulder. He then declares to her that he is the son of her father’s sister, a piece of information that causes Rachel to run immediately and report this fact to her father, Laban. Realizing exactly who Jacob is and what his arrival means for him and his family, he quickly hurries to the well to see the visitor, falling upon him in a hug and kiss. And thus, upon Jacob’s recitation of the details of his lineage and voyage, Laban announces that Jacob is his flesh and blood and implies that he and Jacob possess more than a casual familiar connection. (Hamilton, p256)

I can hear the comments now – “What are you talking about? You said this episode was a copy of the interaction between The Servant and Rebekah. I don’t see any similarities!” And that’s an understandable reaction. This latter portion of the narrative seems to merely skim the surface of the former, as it is shorter, quirkier, and begins under different sets of circumstances. Nevertheless, you must realize there are some immediate parallels between Genesis 24 and Genesis 29:1-14 – 1) someone is commissioned to cross the desert to find a wife from amongst their family members; 2) there is a discussion that occurs at a well; 3) a man meets a woman at a well; and 4) the woman tells her family about meeting the man at the well. But in spite of those seemingly obvious parallels, what is subtly implied must be overtly stated – Jacob equals neither Isaac nor The Servant and Rachel certainly is not Rebekah. In fact, it’s the total other way around.

The means by which the details of Jacob’s meeting of Rachel occur are literally a mirror image of Rebekah’s introduction to Abraham’s house. The roles of the players are completely flipped. Ellen Frankel, in the voice of “Our Mothers” explains the situation this way: “When Abraham’s servant Eliezer devises a test to identify the right wife for Isaac, he’s looking for the following qualities: kindness to strangers and animals, beauty, modesty, and loyalty to family. He finds them all in Rebekah. But when Jacob comes to the same well years later, he finds himself replaying Rebecca’s [her spelling and italics], not Eliezer’s: so instead of waiting for a young woman to approach him, he comes forward to meet her; instead of her watering his animals, he waters hers. When he reveals himself to her, it’s not Rachel but he who weeps.” (Frankel, p50)

Jacob is certainly not his father; the fact that it is he has made this journey on his own and Isaac never sent out any kind of servant to find a wife for his children. He is the “antithesis” of his father in that he is the one present at the meeting of the future spouses and he is the one who prefers activity to passivity. (Alter, p152) Granted, Esau, back in Genesis 28:6-9, took offense to the mere assistance that their parents gave to Jacob concerning where to go to find a wife, but Jacob, considering the fact that he stole the birthright and blessing, was more than happy to get out of the house. Moreover, Jacob is certainly not a mere copy of his mother: having left his family’s tents, he can act of his own accord and allow his inner strength to come to the fore as he both does the shepherds’ jobs for them and initiates the potentially awkward introductions with Rachel and Laban. (Hamilton, p255)

Thus, we approach the end of this passage with a sense of heightened expectations – Jacob has met Rachel, he has sought to prove his worth and his bloodline to her and her father, his uncle Laban, and Laban has declared that he accepts Jacob as his kin by blood. It seems that everything is in order; all that remains is for Rachel to leave her family’s tents to become Jacob’s wife, just as her aunt Rebekah did when The Servant negotiated for her hand in marriage. However, the common factor in both of these stories is Uncle/Father Laban, a man who did his best to negotiate for extra dowry and time before The Servant took his sister away to Isaac’s tents. Jacob has none of the financial backing that The Servant provided in Isaac’s stead, a variation in the two stories that Laban latches onto quite quickly. Jacob the Trickster will come to meet his match in the personage of Laban. (Brueggemann, p253)

We are faced with the question of how to discern the content and purpose of this story in the narrative. We can approach these fourteen verses as purely story; they are the simple continuation of the larger account. Jacob has to go somewhere after meeting God at Bethel, so the logical place for him to go is for him to arrive at Paddan Aram, the tents of his mother’s family. He meets his future wife and her father, demonstrates his value, and places himself at the mercy of Laban. Many commentators mention specifically that they felt that this is the beginning of Jacob’s reaping of the sowing of bad deeds from his past, but to speak of this passage merely in vengeful tones misses the larger picture. To put it rather simply, the show must go on – Jacob must continue fulfilling The Promise, as God commissioned him to do. Moreover, after three chapters of reading about how despicable, deceptive, and power-hungry he seemed to be, it is in this passage that we learn of good, positive aspects to Jacob’s character. Jacob now stands up, all on his own, and does the proper and honorable thing by watering the sheep of his Uncle Laban and approaching Rachel with reverence and awe. However, with such helpful actions, Jacob falls prey to the machinations of Laban; Jacob will get to see what true deception looks like. (Frankel, p51)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home