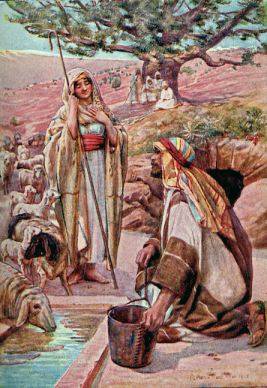

Isaac & Rebekah

Isaac & Rebekah

Or

You’ve Gotta Love Arranged MarriagesAt first glance, this is quite a long chapter – 67 verses of Abraham sending off “his servant” (Eliezer, by most accounts and commentators, and referred to in this lesson primarily as “The Servant”) to locate a wife for Isaac so that the promise of a nation being born through can continue on unabated. Yes, to our contemporary thought processes appears to be quite a quaint social convention of ancient and/or pre-modern times. And yes, as someone rather versed in monarchical political machinations throughout history, I am more than aware of the biological messiness that often arises with marriages between closely related families. However, in all reality, Abraham is engaged in a tried-and-true exercise in nation-building, all dressed up in the guise of finding his son a wife.

Thus, in attempt to expedite and flow smoothly through these culturally delicate, our glimpse into this story in the lives of the Patriarchs will occur from four different perspectives – 1) Abraham & The Servant, 2) The Servant & Rebekah, 3) The Servant & Rebekah’s family, and 4) Isaac & Rebekah. (Brueggemann, p197) The Servant’s eyes will show us what it was like to be sent out on the search for the woman who will continue the promise with Isaac. Through the eyes of Rebekah, we will gaze into what it was like to be the woman being sought after to be the future wife of Isaac. And we will attempt to do our best and wait along with Abraham and Isaac back at the tents, hoping that The servant is either discerning, lucky, or both. Hopefully, throughout this discussion and three-voiced conversation, we will gain a clearer vision of what this story entails for the larger story in Genesis.

“He [Abraham] said to the senior servant in his household [Eliezer], the one in charge of all that he had, ‘I want you to swear by the Lord, the God of heaven and the God of earth, that you will not get a wife for my son from the daughters of the Canaanites, among whom I am living, but will go to my country and my own relatives and get a wife for my son Isaac.’” (Genesis 24:3-4,

TNIV)

From the beginning of this story, the journey the reader takes with Abraham’s servant is one of faith, no different than that of Abraham’s original journey. Abraham declares to The Servant that he must travel back across the whole of the desert, back to Abraham’s homeland, in a possibly vain attempt to locate Isaac’s wife. There can be no stopping midway for a wife from a local girl, since, by marrying a Canaanite woman, the promise could not be properly fulfilled. I would surmise that to have married locally would meant that Isaac would have been able to possess the land through political machinations and not through divine providence and blessing. And if there’s anything that Abraham has (or should have) learned over all of these years is that his and Sarah’s human plans have paled in comparison to God’s and have usually caused more harm than good. Abraham simply isn’t going to settle for anything less than a God-provided miracle, even if he does send The Servant out on this very important mission, as opposed to himself or Isaac.

And listen to this unusual requirement Abraham issues for identifying his future daughter-in-law: “If the woman is unwilling to come back with you, then you will be released from this oath of mine. Only do not take my son back there.” (Genesis 24:8,

TNIV) Abraham declared that an angel of the Lord would be guiding The Servant to any potential marriage candidates and, if they didn’t want to return to see Isaac with The Servant, then she was obviously not the woman for Isaac. Moreover, I find Abraham’s specific declaration that Isaac should not accompany The Servant on the journey to be a curious one. Now, while I don’t want to read too much into the text from my sociological purview, it would seem that Abraham doesn’t want Isaac to be tempted by any Canaanite woman along the way. If you’ve done your math along the way, you’ll remember that Isaac is 37 years old by this time and has just experienced the death of his mother, not to mention having had a near-death experience. Maybe Abraham is fearful that the middle-aged, lonely, and hurting Isaac would be inclined to marry any woman that struck his fancy or that he thought would be good enough. But we can only surmise these things because Abraham simply was not very clear in the instructions that he gave to The Servant, leaving him to his own devices.

“Then he prayed, ‘Lord, God of my master Abraham, make me successful today, and show kindness to my master Abraham. See, I am standing beside this spring, and the daughters of the townspeople are coming out to draw water. May it be that when I say to a girl, ‘Please let down your jar that I may have a drink,’ and she says, ‘Drink, and I’ll water your camels too’ – let her be the one you have chosen for your servant Isaac. By this I will know that you have shown kindness to my master.’” (Genesis 24:12-14,

TNIV)

Now, I don’t know about you, but if I were praying a specific prayer to God to lead me in some difficult task, I’m not sure that I’m going to be requesting that this woman knows how to serve water well to a complete stranger. I understand that he’s looking for certain traits in a wife for Isaac, but The Servant’s desired method of back-and-forth conversation with a woman leaves much to be desired in terms of being effective. (Frankel, p32) However, Ellen Frankel, using the voice of Rebekah, responds to such criticism of The Servant’s methods with these words: “Eliezer’s test was designed to locate a woman discreet enough not to approach a stranger but bold enough to extend herself, once approached by him. This particular combination of character traits – a kind of cagey gumption – is precisely what enabled me to secure Jacob’s future by tricking my husband and my older son out of a birthright. So Eliezer’s angel [Genesis 24:7] obviously knew exactly what she was doing.” (Frankel, p33) It seems that God answered The Servant’s prayers, and as strange as the methodology might seem to us, it brought Rebekah and the servant together, in accordance with God’s plans. (Brueggemann, p198)

And in case you’re interested, I’d like to provide this side note to the general flow of the lesson, a curiosity upon which many commentators took specific note. The Servant launched off from Abraham’s tent with ten camels across the blazing hot Arabian Desert; thus, upon arriving at Aram-Naharaim, The Servant and his camels would be quite parched. A camel could drink up to twenty-five gallons of water to replenish their internal supplies, so The Servant’s prayerful request that the potential spouse for Isaac be willing to water all ten of those camels would be quite a daunting task for anyone to fulfill adequately. (Walton, Matthews, & Chavalas, p56) Robert Alter even goes as far as to make the comparison in his book

Genesis, stating, “This is the closest anyone comes in Genesis to a feat of ‘Homeric’ heroism. … Rebekah hurrying down the steps of the well would have had to be a nonstop blur of motion in order to carry up all this water in her single jug.” (Alter, p116) Rebekah’s overt willingness to achieve this feat would have been an example of chutzpah and physical strength that would have astounded the travel-worn, yet hopeful Servant beyond his wildest expectations.

So, The Servant has found, through angelic and divine direction Rebekah, the woman who is to be the wife of Isaac. From the well, The Servant went to the tents of Rebekah’s family so that he may meet with her (unnamed) Mother and brother Laban (who Jacob will have severe issues with later in Genesis) and persuade Rebekah’s family to permit her to return with him to marry Isaac. Much of the interaction between The Servant and the family revolves around two primary motifs – the ceremonial retelling to Laban and Mother of the scenario in which The Servant met Rebekah and the proffering of gifts as a means of proving Abraham’s wealth and Isaac’s suitability as a potential husband. With the recitation of their meeting, The Servant leaves out only Abraham’s specific directions that relate to the Covenant, an omission that many feel was necessary and proper to not offend those who might hear such seemingly egotistical declarations of divine supremacy. (Plaut, p163 & Alter, p118) Such a speech, though its style and substance sounds overly formal and unnecessary to our contemporary ears, in cultures where stories of familial history such as these were passed along orally, such repetition is quite typical, as it was used as for dramatic effect in an attempt to keep the listener’s interest and to underscore the importance of the details being discussed. (Brueggemann, p198) Moreover, the concept of “bride-price” and “dowry” appear as anachronisms to our societal behaviors, but such customs have been in practice amongst families, whether royalty or otherwise, as a means by which the parents of the betrothed can determine if bride will be taken care of appropriately and if the two families will be able to coexist peacefully (which is why many times arranged marriages were used as political tools to achieve long-sought-for peace). (Walton, Matthews, & Chavalas, p56)

All of the cultural factors present in this story are designed to display the historical importance of this marriage to the listener and reader, since it seems that God has chosen this method to further extend and grow the Patriarchal line that God has promised to Abraham. By sending The Servant back to the land of his relatives, Abraham hoped to locate an appropriate wife for his son Isaac, who had yet to or was unwilling to find a wife amongst the Canaanites. Moreover, the great amount of detail in this story further illustrates how God works in ways that humanity has trouble wrapping its collective and individual minds around. Abraham and The Servant have the greatest understanding of this, which can be seen in the seemingly vague guidelines under which their search was undertaken – the fewer human preferences and wishes present, the greater the reliance upon God.

“When they [The Servant, Rebekah, and her family] got up the next morning, he said, ‘Send me on my way to my master.’ But her brother and her mother replied, ‘Let the girl remain with us ten days or so; then you may go.’ But he said to them, ‘Do not detain me, now that the Lord has granted success to my journey. Send me on my way so I may go to my master.’ Then they said, ‘Let’s call the girl and ask her about it.’ So they called Rebekah and asked her, ‘Will you go with this man?’ ‘I will go,’ she said.” (Genesis 24:55-58,

TNIV)

Standing there in her mother’s tents, Rebekah observes the parley between The Servant and Laban concerning her future, a discussion that she arranged by fulfilling The Servant’s prayerful requirements, a discussion in which, by custom, she has no part whatsoever. However, when it comes time for The Servant to return with Rebekah to Isaac’s tents, her family understandably resists, since her departure meant that they would most likely never see her again. They petition for a ten-day waiting period, to which The Servant responds by declaring that he must return immediately as a way of thanking God for answering his and Abraham’s prayers. But in an instance unparalleled in Near Eastern literature from that time period, the men turn to Rebekah to ask her what she would like to do. Having not been consulted earlier during the exchange of gifts as to whether or not she would like to be married off to Isaac, the fact that The Servant and her family are now asking for her approval is quite unusual and atypical for similar scenarios. (Walton, Matthews, & Chavalas, p56)

On pages 34-35 of her

The Five Books of Miriam, Ellen Frankel provides the following two portions of commentary in dialogue/conversational format to shed some light upon these quite curious events. Read along with me.

Her Mother’s Household

“Our Daughters Ask: Why does the Torah say that ‘The maiden ran and told all this to her mother’s household’ (24:28)? More likely it’s her father’s house.

Wily Rebecca [Frankel’s Spelling] Answers: So much in my story goes against the grain of patriarchal culture: My genealogy’s usually traced through my grandmother Milcah (though Eliezer, whenever he told his side of the story, kept substituting my grandfather’s name). Although the narrator rightly identifies my home as my mother’s household, Eliezer always insisted that he’d been sent to Abraham’s father’s household. But notice that Eliezer gave gifts to my brother and mother, but not to my father. And it was my mother and my brother Laban who negotiated for my hand. And my mother and Laban asked me if I wanted to go off with Eliezer to marry Isaac.

Our Mothers Observe: Even today Middle Eastern and Mediterranean cultures typically don’t grant such privileged status to women. How much more exceptional that the ancient Bible does!”

Rebecca’s Decision

“Our Daughters Ask: Who makes the decision that Rebecca should marry Isaac? Is Rebecca really allowed to decide for herself, as it is written, ‘Will you go with this man?’ (24:58) In most traditional cultures, such things aren’t allowed.

Wily Rebecca Answers: I always suspected that my brother Laban was up to something in asking me for my consent. Maybe he was hoping I’d refuse, so that he could squeeze more of a bride-price from Eliezer. Laban was certainly capable of such crude behavior. Remember that he later extorted from Jacob seven extra years for Rachel’s hand. And I also wonder about my mother’s motives. I suspect that she wanted to keep me home, so she insisted on my consent in the hopes that I would refuse the marriage. She already knew that she’d probably never see me again, never see her grandchildren. But in the end all she got was ten more days with me.

Our Mothers Add: Perhaps she simply wanted to grant Rebecca a voice, something she did not have in her own life. After all, she does not even have a name.”

“Then the servant told Isaac all he had done. Isaac brought her into the tent of his mother Sarah, and he married Rebekah. So she became his wife, and he loved her; and Isaac was comforted after his mother’s death.” (Genesis 24:66-67,

TNIV)

After a long voyage back to Abraham’s old home, meeting Rebekah, negotiating with Rebekah’s family for her hand in marriage to Isaac, and having Rebekah personally decide that she did want to leave home to be Isaac’s wife, The Servant returns home to Abraham’s tents, bringing with him the woman who would help Isaac perpetuate God’s promises to Abraham. And as you read through the events of Rebekah’s approach via camel with Isaac observing her coming as he stands in the fields, you get the impression that Hollywood itself has borrowed from this idyllic scene a few too many times. The scene is almost cliché in how it concludes the journey that is Genesis 24, yet it evokes a sweet and happy tenderness as the coming together of husband and wife is so gently rendered, including Isaac’s comforting in his mother’s tent. (Brueggemann, p199) The long voyage and search have concluded and all parties involved are pleased with the outcome, one in which every possible consideration and plea that had been made prior to the journey being made was met to its fullest extent. Rebekah approached her husband veiled, in the cultural tradition surrounding marriage (Plaut, p166), and Isaac brought her into his deceased mother’s tent, so that Rebekah could take her place as the family matriarch. (Alter, p123)

The line can now continue and can do so without all of the domestic discord that surrounded Abraham, Sarah, Hagar, Ishmael, and Isaac for those great many years. Isaac, above all, must have been quite pleased in the amiable outcome of the search for his wife, unbeknownst to the domestic trauma that will arise between his twin sons in the next chapter.

/images/scan0024.jpg)